Recently, I have been having some fun with the algorithmic challenges from one of the Algorithms courses on Coursera. The programming language I like to use for this kind of things is ruby.

When designing an algorithm it’s important for me to understand why brute force doesn’t work. I like to count the reasons why that approach is not feasible. One way of doing that is to write a naïve implementation of the algorithm under study and make considerations about its running time. Let me give you an example.

A sample problem

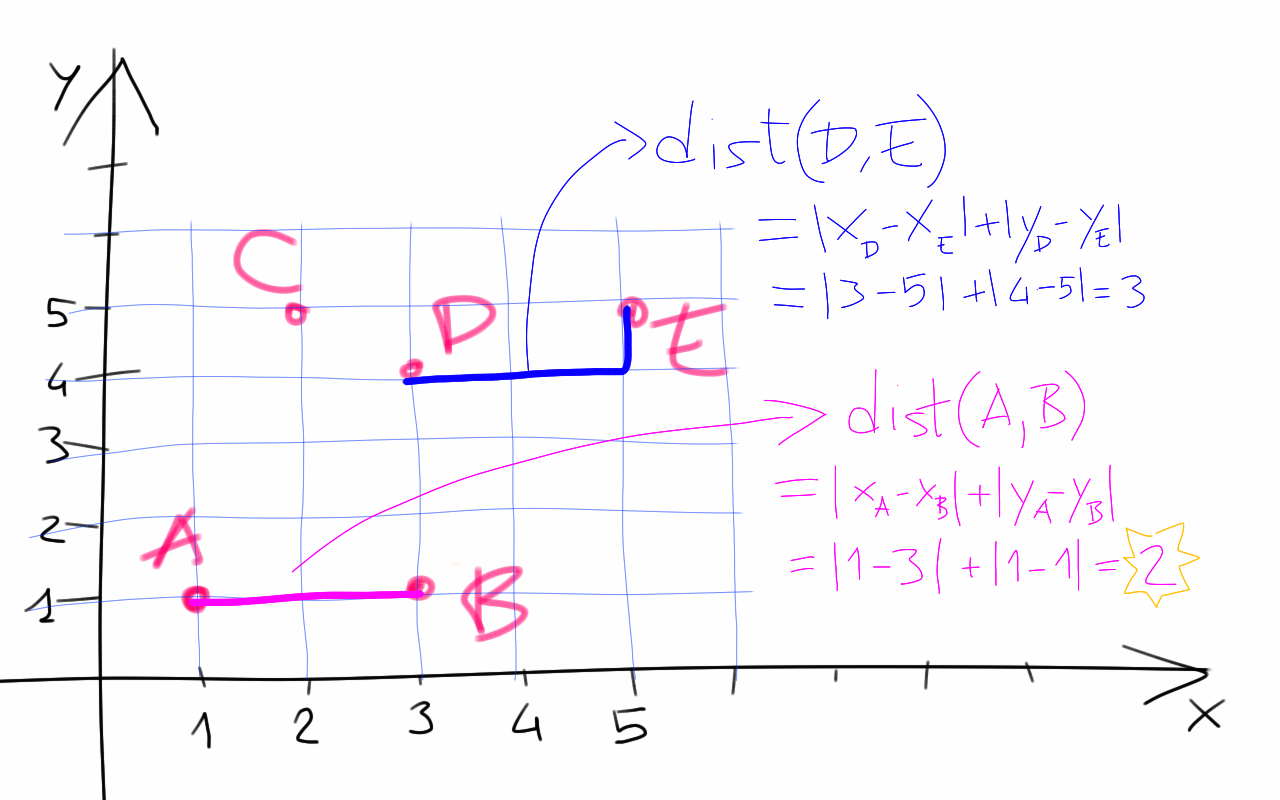

We are given a set of 2D points with integer coordinates. We define the distance between two points u,v as the Manhattan distance

dist(u,v) = |x_u - x_v| + |y_u - y_v|

where |n| is the absolute value of n.

Figure 1. We give a visual representation of the distance between two points as defined above and work out the computation for points A(1,1), B(3,1) and D(3,4), E(5,5)

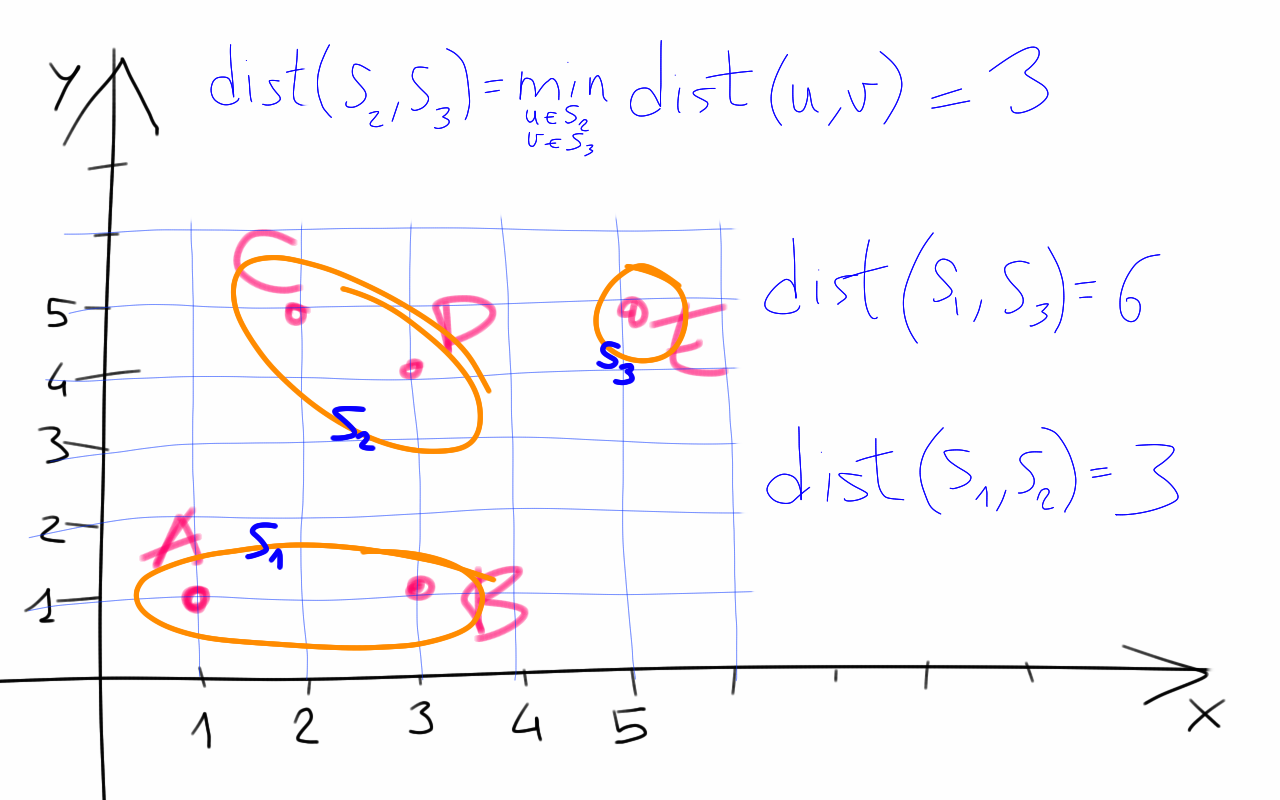

Our task is to group the given points so that the minimum distance between any two groups - let’s call them clusters - is at least 3. In other words, if two points have distance less than 3, then we want them to be in the same cluster.

Figure 2. The figure shows a grouping of the points into clusters such that the distance between each cluster is at least 3. We define the distance between two clusters S_i, S_j as the minimum distance between u and v where u ∊ S_i and v ∊ S_j.

for i in 1..n

for j in i+1..n

if dist(i,j) < 3

merge_clusters(i, j)

Now, it’s not clear how exactly we are going to keep track of which cluster a point is in at any given time, but even assuming we can do that efficiently with respect to the size of the problem - i.e. the number of points - we have a more urgent issue to deal with.

The more urgent issue

The total number of pairs in a set of n points happens to be n(n-1)/2, which means that the number of pairs we need to go through grows quadratically with respect to the number of points. This implies that the computational cost of our brute force implementation is at least O(n²). Let’s get a feel for that.

Try running the following ruby script for increasing values of size up to 10^5 - name the file loop.rb for future reference.

size = <your value here>

a = (1..size).map{ [rand(1000), rand(1000)] }

def dist(u,v)

(u[0] - v[0]).abs + (u[1] - v[1]).abs

end

a.each_with_index {|u,i|

print "\r#{i}" if i % 100 == 0

a[i + 1..-1].each_with_index {|v,j|

dist(u,v) < 3

}

}

On my machine the running time factor between size = 10^4 and size = 10^5 is about 100. In particular, going through the nested for-loop with 100000 elements takes over 20 minutes. And we are not even computing the clusters yet!

So I’m thinking, maybe there’s a better way of dealing with this, maybe we don’t need to go through the array twice. On the other hand, maybe an interpreted language like ruby is just not the right tool for the job.

If only we could test this assumption without too much effort…

Meet Crystal!

A friend recently told me about the Crystal language. He was so excited about it that I thought “I should really check that out”. Let me tell you why this looks like a good moment to do that.

Crystal is a compiled language designed to achieve high performance with low memory footprint. (One of) The killer feature(s) is the syntax. Crystal syntax is so similar to ruby that you might be able to convert your favourite ruby scripts with very little effort - especially if they are self-contained.

Now, that sounds a lot like what we want here: we have a self-contained ruby script, and we want it to run faster!

So after installing Crystal, I tried

crystal loop.rb - yes, just like that.

Our script happens to be fully compatible with Crystal’s specification, so the crystal binary is happy to compile it and run it at once. Sadly, the runtime for size = 100000 is still over 12 minutes…

Is that it? Not really, the getting started guide to Crystal recommends you compile your source code with the --release flag once you’re happy with it.

crystal build loop.rb --release

This produces a blazing fast loop executable that runs in under 70 seconds. We just cut the running time by a factor of 20 and all we had to do was to compile and run our code with Crystal. Awesome!

Considerations

I hope you got to appreciate how Crystal can enhance the performance of our code without affecting our productivity.

And we’ve only scratched the surface! The language has way more to offer. Among other things, Crystal comes with a smart, non-obtrusive type system that prevents a wide range of little bugs from appearing in our code.

So next time you’re faced with a computational challenge, why don’t you give Crystal a try!

But we’re not done yet

If you’re still reading, then you probably noticed I cheated a bit. I gave the outline of a sub-optimal brute force solution, and didn’t even bother providing the full implementation of the clustering algorithm. I leave that to you for now, but I hope I’ll be able to follow up on that soon.

And in case you’re wondering “Can we do any better than the brute force implementation?” the answer is yes, we can indeed! In fact, we should be able to squeeze the running time to O(n) times the cost of merging two clusters.

Benchmark

For the record, here is a table summarizing the running time of three different implementations.

| Language | Running time |

|---|---|

| Ruby | ~23 minutes |

| Node | 3.5 minutes |

| Crystal | 1.1 minutes |

And here is the source code used to generate the benchmark data above.

References

- Crystal lang official home page

- A nice introduction to clustering

I hope you enjoyed the read! You can share your experiences with Crystal scripting in the comments section below.