Introduction

Christmas 2020 came with quite an exceptional gift: a major Ruby release. Among the most anticipated features of this new version is the experimental support for actor-based concurrency and parallelism in the shape of Ractors: light-weight concurrency primitives that share no state and communicate with each other by passing messages.

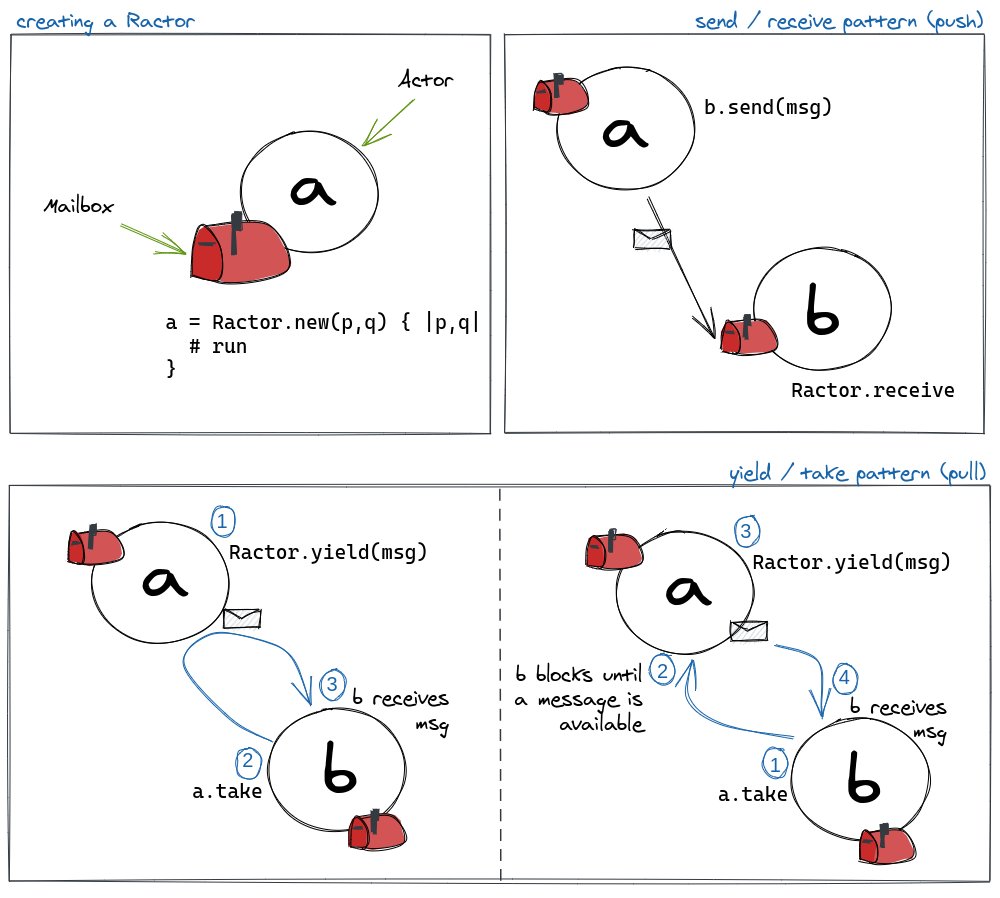

Figure 1. A visual overview of the Ractor API. The API supports both pull and push communication patterns between actors.

In classic Ruby style, the Ractor API comes with a set of utilities that make achieving simple things trivial, while also allowing power users to build more complex systems.

Figure 1 shows an overview of the basic methods of the API.

Ractor.newcreates a new actor and its mailbox. The main gotcha here is: the block passed toRactor.newdoes not close over the variable scope it was called in. Instead, any variable we want to be available inside the block has to be passed tonewas an argument (Figure 1, top-left corner). Check out the documentation for more details on block isolation.Ractor#sendis a non-blocking method. It enqueues a message in the target actor’s mailbox (Figure 1, top-right corner). The receiver may dequeue messages from the mailbox by callingRactor.receive. If the mailbox is empty, then the caller will block until a message is delivered.- Both

Ractor.yieldandRactor#takeare blocking methods. The bottom end of Figure 1 shows two possible scenarios. In the bottom-left corner, actorayields a value and waits untilbinvokesa.take.breceives the message instantly. In the bottom-right corner,binvokesa.takefirst, and hangs untilacallsRactor.yield(msg).

You can check out the official readme for some simple examples and to further explore the API.

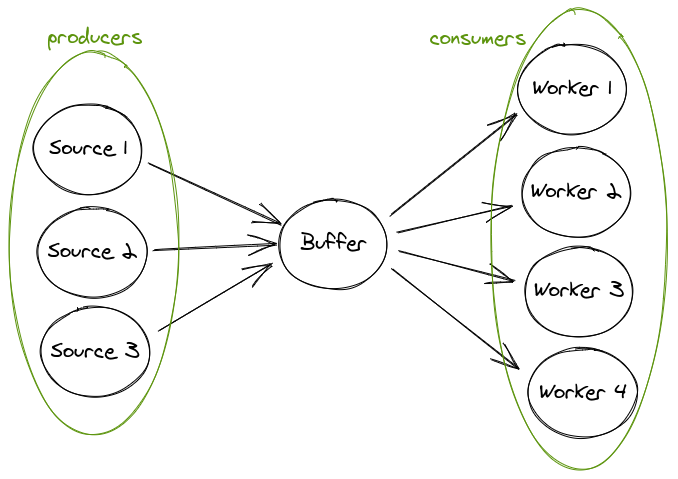

In this article, we’ll focus on defining some reusable components to implement the parallel producer(s) / consumer(s) architecture shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A diagram representing the parallel data flow between data sources and workers in a producer / consumer architecture.

Building blocks

Source

Let’s define a function source that returns an actor producing values in a loop and sending them to a target actor.

def source(generator, target:, name: nil)

Ractor.new(generator, target, name: name) do |generator, target|

loop do

target.send generator.next

end

end

end

Note how we can make a source stateful by encapsulating state in the generator object passed in at initialisation time.

Buffer

The buffer function returns an actor that yields each message received in its mailbox for any actor to take.

def buffer

Ractor.new do

loop do

Ractor.yield Ractor.receive

end

end

end

Closer look. Ractor.yield is a blocking call, meaning messages will keep on queuing up in the buffer actor’s mailbox while it waits for another actor to take the yielded message. That’s OK, as the capacity of an actor’s mailbox is quite large, but heads up: although the mailbox can grow arbitrarily on paper, its size is still constrained by the host machine’s memory. If the rate of incoming messages for an actor consistently exceeds the rate at which the actor consumes them, then your application will eventually run out of memory and crash 😱

Worker

Our worker function takes a source actor and a behaviour object as an argument.

def worker(behaviour, source:, name: nil)

Ractor.new(behaviour, source, name: name) do |behaviour, source|

state = behaviour.init_state

loop do

state = behaviour.receive(source.take, state)

end

end

end

behaviour defines the initial state of the actor and exposes a receive method that will transform a received message and the current state of the actor into its next state.

With this little code, we have enough infrastructure to implement a parallel producer(s) / consumer(s) architecture.

Closer look. Note how the implementation above

- decouples producers and consumers, making it possible, among other things, to dynamically scale up and down the number of actors on each side of the buffer.

- ensures optimal workers utilisation: as soon as a worker is idle, it will invoke

takeon the buffer. This guarantees that no worker will spend time idling if work is available.

Let’s bring this to life with an example.

Case study: parallel primality test

Let’s build an application where randomly generated numbers are tested for primality in a parallel fashion. We’ll rely on the built in Integer#prime? method to keep the complexity to a minimum (docs).

First, we define a module to generate random integer values in a given range

|

|

Note how we’ve introduced a random delay on line 4, to avoid flooding the buffer’s mailbox.

Challenge. Can you guess what happens if you remove the sleep statement?

Now that we have a generator, we can think about the workers’ behaviour. We’ll make it so that every worker actor encapsulates its own cache mapping integers to a boolean indicating whether they are prime. This might seem somewhat contrived, as ideally actors would share the same cache to avoid repeating work done by other workers, but in practice you’ll find this is a pretty common trade-off that keeps complexity low while providing some caching benefit.

This also demonstrates a common approach to actor state management.

|

|

The code on line 7 is a good showcase of Ruby’s pattern matching functionality.

- In case of cache miss (line 8), we bind the integer value to be tested to

mand update the cache (line 9). - In case of cache hit,

is_primebinds the cached value for the primality test.

Remember that receive must return the up-to-date cache (line 13), so that the worker actor can update its internal state.

OK, we now have all the modules we need to put a producer / consumer system together. Let’s start with a single source and a single worker.

bfr = buffer

source(RandInt, target: bfr)

worker(PrimeTest, source: bfr)

As easy as that. Note how we have to define the buffer first, as that needs to be known to both producers and consumers.

If you try running the code now, you’ll get an underwhelming result: the application will terminate immediately. This is because a Ruby 3.0 application will terminate as soon as the main Ractor terminates. The main Ractor is the first actor invoked by the interpreter (docs) and drives the execution of our code.

To keep our concurrent application running, we can suspend the main Ractor by calling sleep once the other actors have been spawned.

sleep # the last line of our main file

Scaling the topology

To scale the actor topology up to a larger number of sources and workers (e.g. 2 and 5), our code could be updated as follows.

bfr = buffer

(1..2).map { |i|

source(RandInt, target: bfr, name: "source_#{i}")

}

(1..5).map { |i|

worker(PrimeTest, source: bfr, name: "worker_#{i}")

}

Note how we are passing a name to sources and workers: a Ractor’s name gives us a human-readable identifier that we can use for logging and monitoring purposes.

No matter where you are in the code, Ractor.current.name will always resolve to the name of the actor running it.

Challenge. You might be wondering: what do I do with the work completed by the workers? That’s up for you to decide, as their behaviour can be encapsulated in the behaviour object passed at initialisation time. For example, you might turn PrimeTest into a class, initialise it with a target aggregator actor and send {integer, is_prime} tuples to that actor from within the #receive method.

This concludes our tour of Ruby 3.0 Ractors. You can find the full case study source code on github. I hope this inspires you to give Ractors a go 🚀

Further reading

- Official documentation for Ruby Ractors

- On the producer-consumer problem - Wikipedia

- If you haven’t tried Ruby’s pattern matching feature yet, then I recommend you take a look at this great guide by Noppakun Wongsrinoppakun

- My Struct game needed a refresher. I found this how-to by Jesus Castello illuminating.

Thanks for reading, I hope you found this useful. You can share your experiences with Ractors and parallelism in Ruby in the comments section below.

Also, please let me know if you’d like to read more about Ractors on this blog: we’ve only scratched the surface on the topic, and I’d love to spend more time investigating event-driven architectures.